Crosscutting Concepts

Powerful lenses for sensemaking

by Jeffrey Nordine

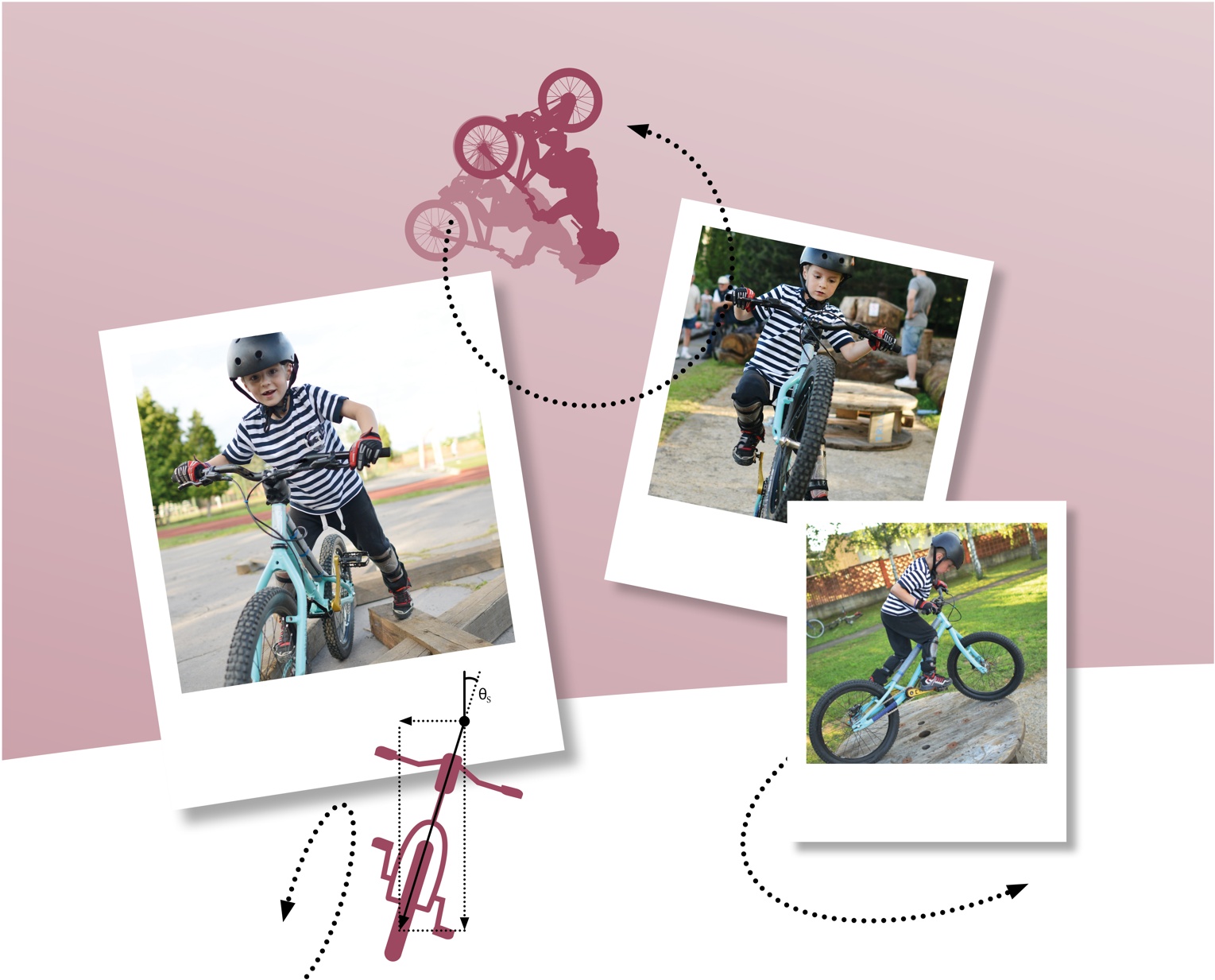

The other day, my 5-year-old son and I were riding our bicycles to his school. Along the way he asked me, “Dad, why don’t bicycles fall over when people ride them?” As a physics educator who’d rather be on a bicycle than almost anywhere else, I was beaming with pride. I was also excited because I’d thought about this question before, and thought I had a good answer. After telling him what a great question he’d asked, I decided to share with him my ideas about why this happens. He wasn’t convinced. Then, I asked him what I should have asked in the first place, which was, “How could we find out why bicycles don’t fall over when people ride them?” Not realizing it at the time, our conversation was a wonderful example of the role so-called “crosscutting concepts” play in making sense of the world around us.

The crosscutting concepts (CCCs) are a set of conceptual tools identified within the US Framework for K-12 Science Education by the National Research Council in 2012. They are called “crosscutting” because they are broadly used across all disciplines of science and engineering. The seven CCCs include:

- PATTERNS Recognizing and describing patterns in nature sets the stage for explaining and predicting phenomena.

- CAUSE AND EFFECT: MECHANISM AND EXPLANATION A central part of science is determining the causes of events; identifying the mechanism underlying those causes sets the stage for making predictions.

- SCALE, PROPORTION, AND QUANTITY Systems behave differently at different scales; considering relationships between scale, proportion, and quantity is critical across science disciplines.

- SYSTEMS AND SYSTEM MODELS Clearly identifying the system under study sets the stage for constructing models useful for understanding and predicting behavior.

- ENERGY AND MATTER Flows, cycles, and conservation. Some quantities are conserved, and energy and matter are two of the most important for understanding everyday phenomena and problems.

- STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION The properties and functions of systems are determined by their physical characteristics.

- STABILITY AND CHANGE Identifying the conditions for stability and quantifying rates of change helps to understand the behavior of systems.

As a set of powerful conceptual tools certainly used by all scientists, they are perhaps poorly named. The name implies they are useful because they cut across disciplines and somehow bring coherence to the science curriculum by connecting across disciplinary boundaries, but I (along with many other colleagues) argue that their power is most plainly seen when used within the boundaries of single science disciplines. CCCs have the power to strengthen science teaching and learning within a discipline in two primary ways:

- making explicit parts of doing science that have long been implicit, and

- providing learners with a set of complementary conceptual lenses on phenomena.

Making the implicit explicit

When my son asked his question, he blended three important ways of thinking together. First, he used his intuitive understanding of what he will later come to know as the law of gravitation – that is, the Earth pulls all objects directly downward. He knows from his 5 years of experience doing things like building with blocks that something shaped like a bicycle will usually fall over on its side rather than stand up on its narrow wheels. Second, he formulated a question that could be answered by a scientific investigation. Of course, he’s not thinking in these terms explicitly but doing a fundamental job of the scientist – asking why. Third, he is recognizing an important pattern – that bicycles do tend to fall over when they are stationary, but they do not fall over when someone is riding it. Recognizing this pattern focuses his attention on the role that a person riding the bicycle has in keeping it upright.

Though he has yet to begin formal science instruction, my son’s question exemplifies the vision of so-called “three-dimensional” science learning described in the US Framework for K-12 Science Education. In this vision, science learning involves developing an understanding of and ability to use three different dimensions of science learning: science and engineering practices (SEPs), disciplinary core ideas (DCIs), and CCCs. SEPs include practices such as asking testable questions, using models, and constructing arguments; DCIs are the most central ideas within each science discipline, such as the nature of matter, plate tectonics, and evolution through natural selection. Each of these dimensions describes a set of conceptual tools indispensable for doing science. Research in science education has long emphasized the importance of blending science content and practice, and while the Framework is hardly the first document to recognize the importance of ideas like systems and scale in science, its explicit inclusion of CCCs recognizes them as a set of conceptual tools distinct from science practices and principles and also a critical part of doing science.

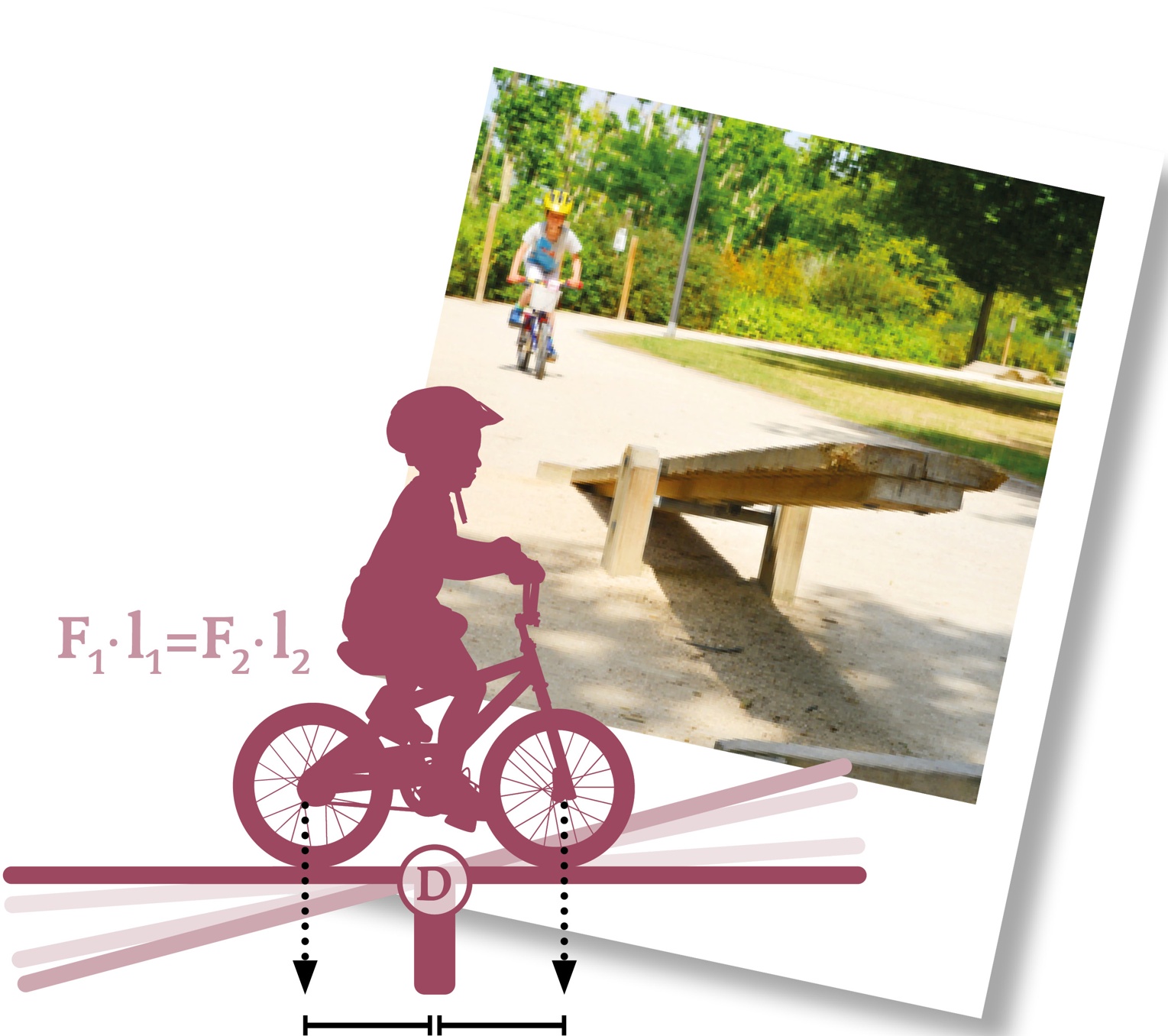

If my son were to actually design and conduct an investigation (SEP) to answer his question, the goal would be to uncover the mechanism (DCI) that explains a causal link (CCC) between a rider’s actions on a bicycle and staying upright. Note that in both asking his initial question and finding an answer, all three science dimensions are required. The CCCs include a set of conceptual tools critical in connecting science content and practices to make sense of phenomena and solve problems, and explicitly including them in science instruction may be particularly important for broadening participation in science.

Complementary conceptual lenses

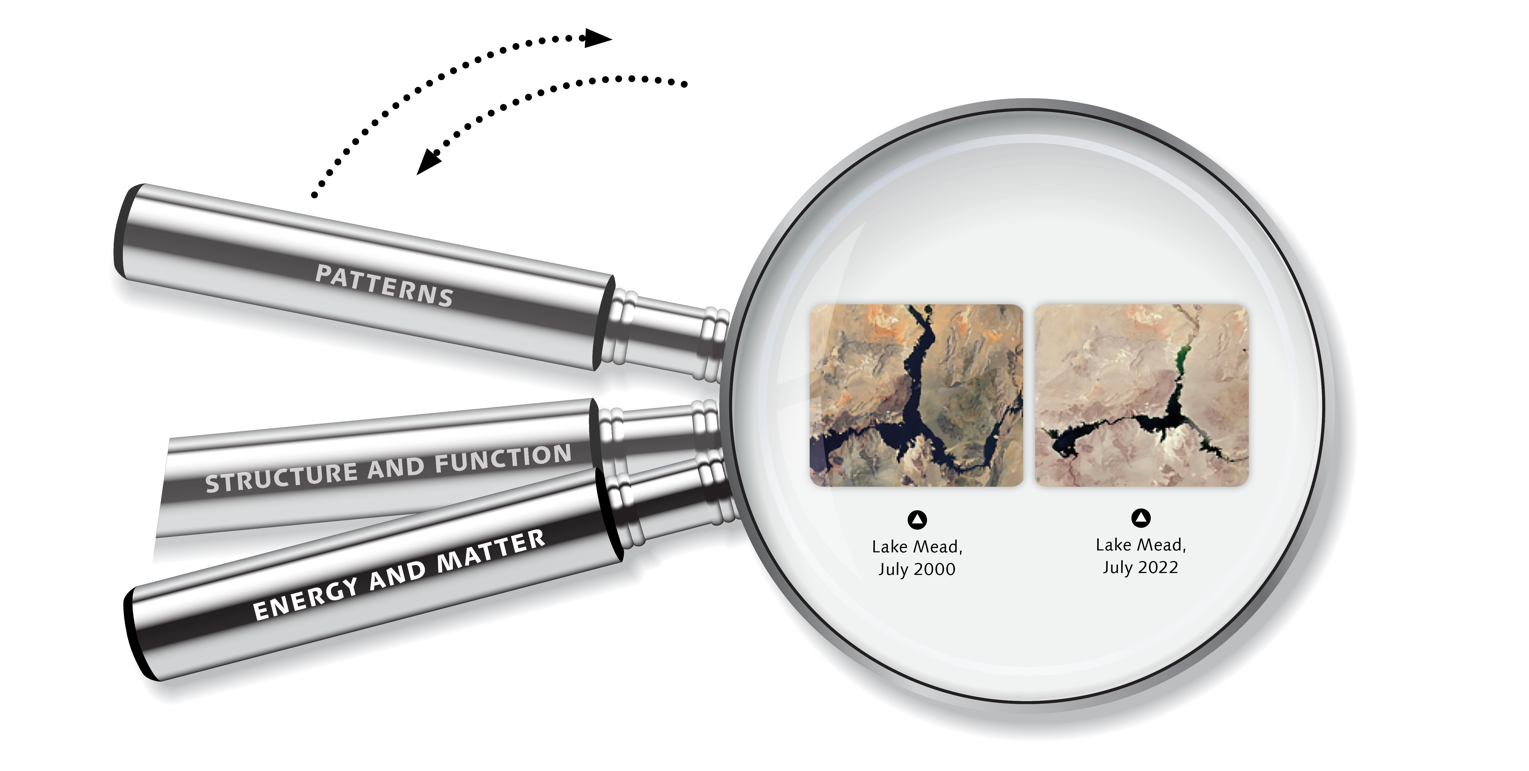

An optical lens shapes the way our eyes see objects around us – they sharpen, magnify, or shrink regions of the light that reaches our eyes and thereby affect how our eyes process visual information. CCCs can be regarded as conceptual lenses because they shape the way we think about phenomena and problems. By helping us to focus on key aspects of phenomena and problems, CCCs have the potential to focus attention and frame thinking so learners engage in noticing and questioning, thereby setting the stage for deeper insight. To illustrate how CCCs can prompt deeper thinking, consider Lake Mead in the western United States. The lake is a reservoir formed by the Hoover Damon the Colorado River, and a major source of water for people and farmland in the region. In recent years, the water level in Lake Mead has been severely declining.

The CCCs provide conceptual tools for more fully understanding why the decline is happening and informing decisions about what to do in response. Using a systems lens prompts questions about the boundaries of the lake system, how water flows into and out of it, what different subsystems are involved and how they are connected, etc. From an energy and matter conservation perspective, we consider the role of sunlight and ambient temperature, water phase transitions, and expansion/contraction of water. Using a structure and function lens prompts consideration of how the structure of the landforms in and around the lake influence factors such as the surface area to volume of the lake, which in turn affects other key variables like evaporation rates.

Applying multiple CCCs to the same phenomenon provides a complementary set of observations and questions that can ultimately enrich our understanding. In a classroom setting, CCCs are both an entry to and outcome of science learning. CCCs serve as a powerful entry point to learning, as CCCs are often more clearly relatable to learners’ experiences outside of the classroom. For example, humans have an innate ability to look for patterns and to look for causal relationships in their environment, as these abilities are critical for survival. As a result, applying these lenses to phenomena and problems can feel intuitive for learners. Not all CCCs are this way – energy and matter conservation, for example, is a lens that must be developed over the course of years. As learners use CCCs in conjunction with science ideas and practices, they develop their understanding of both the phenomenon/problem under investigation and the conceptual tools they apply. With explicit instruction and repeated opportunities to use a variety of CCC lenses over time, learners’ sophistication in understanding and using CCCS grows.

Analogs in Germany

The term “crosscutting concept” refers to a specific set of seven conceptual tools that appear within the US Framework, yet the role that CCCs play in supporting learners in doing science is broadly applicable. While there are no CCCs in the German Bildungsstandards, the structure of the Bildungsstandards is in some key ways similar to the US Framework, and considering these similarities may be productive for how researchers can better support science teachers and students.

In comparing the Framework and the Bildungsstandards for the science disciplines, the SEPs correspond quite nicely to the competence area Erkenntnisgewinnung, since both describe what scientists do in order to build new knowledge. The DCIs align with the competence area Fachwissen, since both identify science ideas that learners should know and use. The best analog for CCCs is probably the Basiskonzepte, since both describe a set of ideas broadly useful across a range of topics and contexts. Further, several CCCs are explicitly identified as Basiskonzepte, such as: systems, structure and function, and matter and energy conservation. Yet, an important difference is that the Basiskonzepte differ between disciplines (biology, chemistry, and physics) and vary across school levels (Mittleren Schulabschluss and Allgemeine Hochschulreife) – though significant similarities also exist across disciplines and levels as well (for example, energy appears in some form across all disciplines). From a practical perspective, perhaps the greatest similarity between the CCCs and the Basiskonzepte is that teachers often feel confused about the role they should play in their instruction.

Even though the CCCs and Basiskonzepte are not completely analogous to each other, both may play similar roles in strengthening science teaching and learning by:

- making explicit parts of doing science that have long been implicit and

- providing learners with a complementary set of conceptual lenses on phenomena that provide multiple entry points to sensemaking.

How can researchers support teachers?

The CCCs are an important part of doing science, yet their inclusion of the CCCs in the US Framework was quite remarkable since the empirical research base into student learning about these ideas is relatively thin. The authors of the Framework acknowledge this, writing, “The research base on learning and teaching the crosscutting concepts is limited. For this reason, the progressions we describe should be treated as hypotheses that require further empirical investigation.” Since the publication of the Framework, some important work has been done to clarify the role that CCCs play in supporting science learning (e.g., Rivet et al., 2016), yet a recent review of literature identified only a few studies that explored the effects of explicit CCC instruction. At the same time, other researchers have questioned the value of CCCs as a dimension of science learning. The end result is that researchers do not currently have a clear message for teachers regarding the role that CCCs play in strengthening science learning or how students can be supported in learning and using these important ways of thinking.

Although the CCCs as a specific set of conceptual tools exist only in the US curriculum framework, most of them appear as Basiskonzepte in the German curriculum, and teachers in both settings are asked to support students in using these ideas in conjunction with science practices and principles in order to make sense of phenomena across a range of contexts. As researchers, we can better support teachers by empirically investigating how these important ideas can be built over time and used consistently across contexts. If a central goal of science education is to support students in transferring their understanding to new situations and learning efficiently after the conclusion of formal instruction, science education researchers should prioritize investigating how learners build and use conceptual tools that have widespread applicability and serve as powerful lenses for sensemaking.

Nordine, J., & Lee, O. (Eds.) (2021). Crosscutting concepts: Strengthening science and engineering learning. National Science Teaching Association.

Über den Autor:

Prof. Jeffrey Nordine hat an der University of Michigan in der Arbeitsgruppe von Prof. Dr. Joseph S. Krajcik zur Entwicklung einer Unterrichtseinheit „Energie“ promoviert. Danach war er als Assistant Professor for Physics Education am Trinity College in San Antonio, TX, USA, und als Chief Scientist des San Antonio Children‘s Museum, TX, USA, tätig. Im Jahr 2016 siedelte er nach Deutschland über. Hier war er bis vor kurzem stellvertretender Direktor der Abteilung Didaktik der Physik am IPN. Derzeit ist er Associate Professor of Science Education an der University of Iowa, USA. ipnjournal@leibniz-ipn.de